I became familiar with this term in and around my early adolescence. I began to conceptualize it more clearly once I developed a more clear sense of musical taste. As this became clearer, I came to simply associate it with bands making the “big time” and sacrificing a lot of their creative and artistic integrity as a result.

Additionally, I came to view it as the process wherein a band betrays a core following (i.e. a fanbase) by making compromises contrary to the wishes of their audience. Or where they decide to betray their own artistic interests for the sake of appeasing the record label’s desire to sell units.

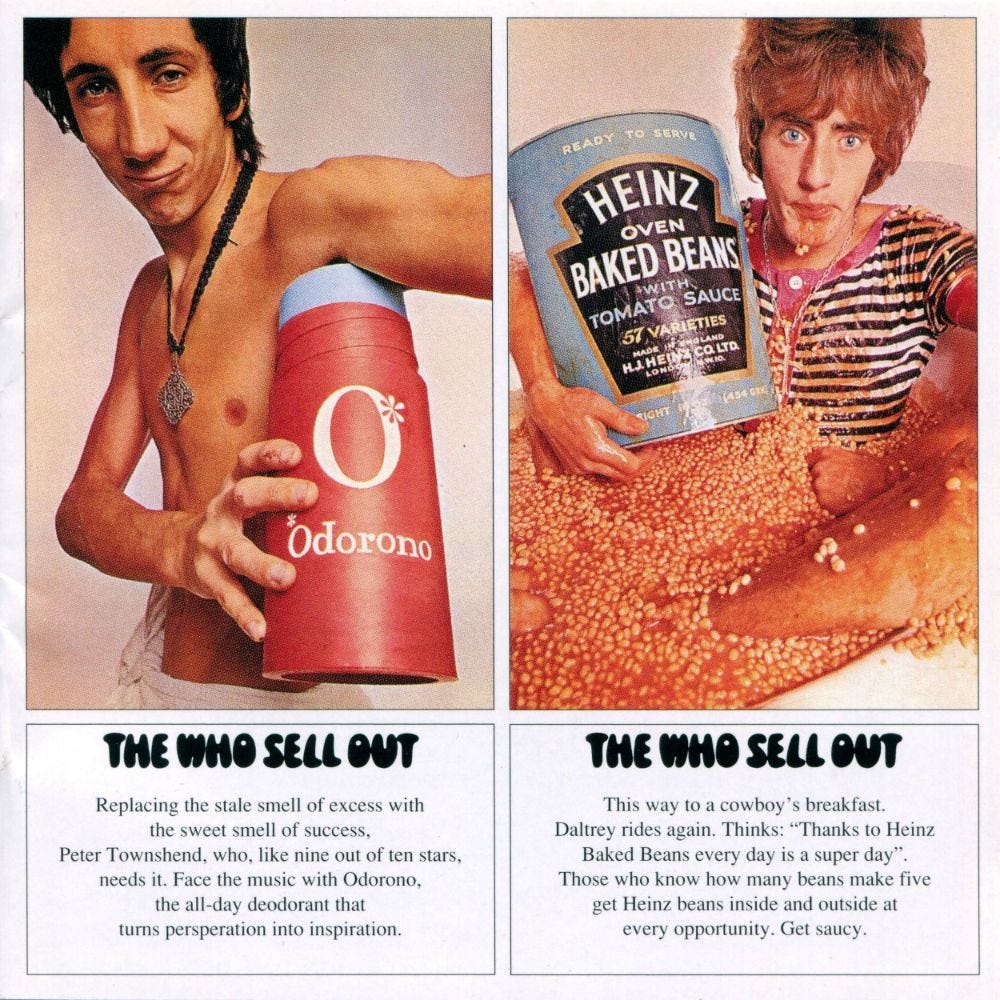

The Who put out an acclaimed album in late 1967. Entitled The Who Sell Out, it was a concept album intended to satirize and poke fun at overt commercialization. The album was presented as a fictitious radio broadcast, full of advertising jingles interspersed with real songs.

Ironically, this was put forth by a band who already enjoyed a large degree of commercial success, along with fellow “Brit Invasion” bands The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Kinks. The iconic cover, which shows members Roger Daltrey and Pete Townsend engaged in blatant product placement, was both a piss-take and a blunt admission of commercialism.

This is not to say that commerce gained from professional musicianship is bad. Nor is filling the venue capacity for a show (i.e. Dublin gig sold out) is bad. It appeases certain factors of existing audience demand. Indeed, the creation and broadcasting of all great music historically has never been a mere product of an “imagination”.

To make that manifest much “boring work” needs to be done. Bands need finances, money, cheques, and potential generous donors in order to make sure that the resources they want to record or perform can be paid and provided for. It is certainly not something I want to consider whilst listening to a record like Stained Class or Blessed Are The Sick, but more than certainly had to be considered by its creators.

It is when you consider the technicalities of such things that it becomes more understandable why bands almost “have to” make a decision which pisses listeners off. Rob Halford, in his “Confess” autobiography states that the metal pioneers felt compromised when they took on an offer to appear on Top Of The Pops at the expense of turning up late for a concert towards the end of the 1970’s.

It was a clear example of a band making an awkward decision which they felt to be unpleasant. One that yielded to the interests of the BBC rather than individual ticket holders who had spent their money to go and see them play live. A decision that asks a critical question; do you continue appeasing fans with the risk of less opportunity, or do you yield to money power knowing that there’s a risk of being more malleable?

In some ways, one has to cut them some slack. On their 1980 album British Steel, the band had a memorable anthem in every song. The sound was singular and catchy, but with an aggressive and hard edge. It was their most accessible work overall today, led by songs such as “Breaking The Law”, “Living After Midnight” and “United”. Yet it was still blunt, authentic, an engine of a band running on full steam, yet to release other genre-defining greats such as 1982’s Screaming For Vengeance and 1990’s Painkiller.

Metallica made a similar decision in the late 1980’s, when metal music had more thoroughly conceptualized itself and was far less embryonic. When “One” from their And Justice For All… album attracted heavy MTV airplay, accompanied by a music video, this was seen as the beginning of a great betrayal by “die-hard” fans of the band.

By the turn of the 1990’s, the band enjoyed huge commercial success through “The Black Album”, and had “matured” in the eyes of the mainstream music press. This came at the expense of much of their original attitude and creativity, amidst a cultural paradigm shift where “alternative rock” and the grunge movement was ushered towards the public spotlight.

To this day Metallica are far more of a PR brand than an actual band, one that literally runs on the exhaust fumes of old glories. Creatively they are a done deal, but commercially they are far more greatly integrated into the corporate Leviathan that is the music industry than in the “hungry years” of the 1980’s.

The mainstream will look on the passing of this period as the next chapter of the “success story”. As far as creative vitality is concerned, And Justice For All… should be viewed as the sign of a band who found themselves on the cusp of mainstream success, soon to transform into a mega-selling juggernaut.

We should consider a band who now enjoy cult status, but whose potential for growth at the time was apparently spurned by the influencers of their time; doom pioneers Pentagram. Having allegedly courted the attention of KISS, the quartet were apparently asked to perform in front of lea members Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley. What should have been the “big break” went less well than expected, and singer Bobby Liebling claimed;

"They said the bass player has too bad acne, the guitar player looks like a statue, the singer is ugly, and the drummer is fat," he recalled, adding that he believes Simmons and Stanley still liked his band's music.”

Indeed, KISS are the most legendary types for shilling, a template for how a purely commerce driven band do business. Driven by the rabid following of the “KISS Army” throughout the 1970’s, to this day you can purchase anything from a KISS mug to a KISS coffin. Notably, the late Dimebag Darrell of Pantera fame was put to rest in a bespoke “Kiss Casket”.

Whilst the rumour that KISS offered to buy two of Pentagram’s songs has never been confirmed in any official capacity, both this and their meeting would suggest that the New York badger cosplay entrepreneurs were clearly more firmly entrenched in bolstering their showbiz facade.

If they were not vampirizing the talents of a band who were undoubtedly better musically, then according to the above quote they were most certainly gatekeeping the access that a then hopeful “up-and-coming” band might have. Such access for Pentagram was seemingly denied on the basis of their image being “unmarketable”.

Though unverified and not possible to take such quotations for granted, one thing is clear; KISS had an image which succeeded, whilst Pentagram did not, and quality and essence of content was not a final outcome in what determines that kind of success. The latter band would finally get a break of their own, on the back of the what became “doom metal” in the 1980’s, and the 2011 documentary film Last Days Here.

In a band like KISS one sees a much more blatant sense of opportunism that speaks far more louder than the musical content, a pure affront of showbiz and mercantilism under which the music is buried. That is not to say that KISS lack any good material, but it is to say that top of their list of “principles” is to make money, with all other considerations secondary.

One can at least commend them for not being dishonest. They were just as much, if not far more about showbiz than they were about content and the essence of the music that they were putting together. One would likely say that this is the same case for many an unquestioning fan of well established acts of “rock royalty”.